Home | Women in Sport | Women in Canadian Sport 1867-Present

Golden Age of women in Sport 1920's - 1930's

PreviousNext

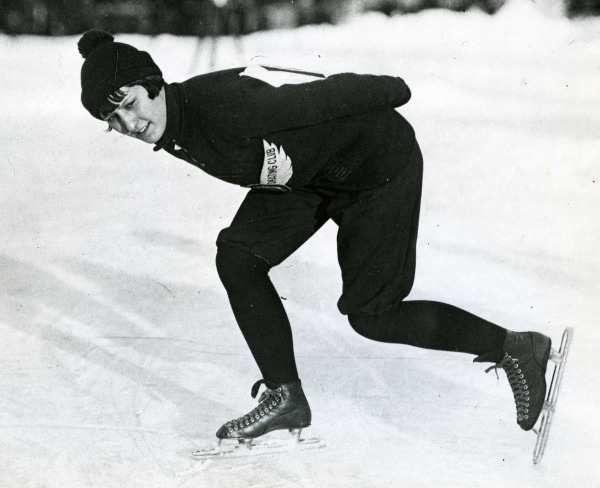

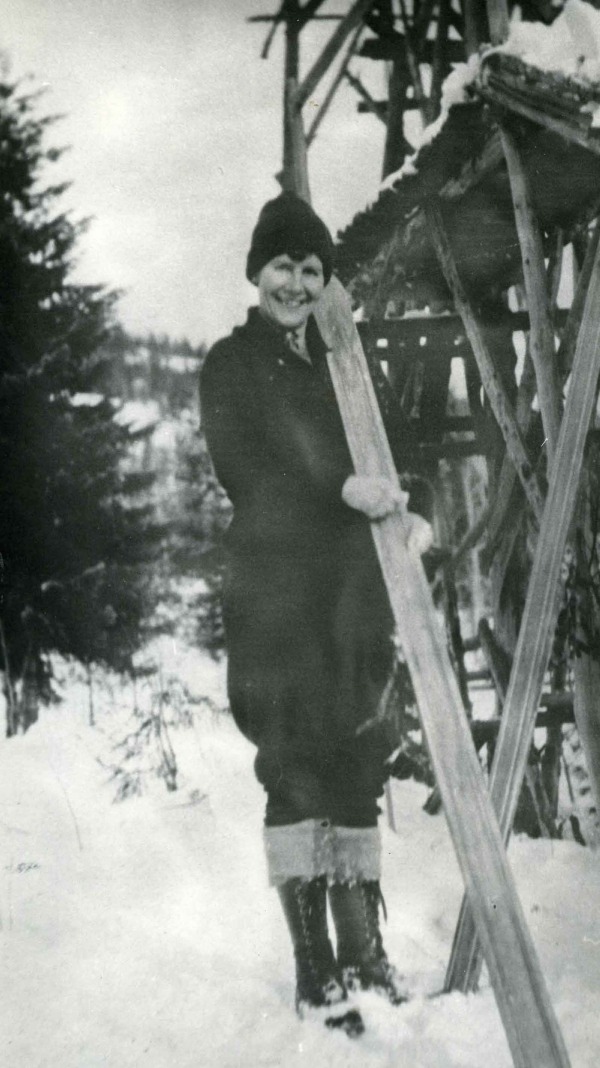

The years spanning 1920 to 1935 have been described as a 'golden age' for Canadian women in sport. Achieving competitive excellence with increasing regularity in sports from which they had historically been excluded, in some cases women literally took a leap of faith to prove they possessed the speed and strength to become champions. In 1922, sixteen year old Isabel Coursier captured the women's world championship title in ski jumping, speeding down the 'Boy's Hill' at Mount Revelstoke without holding the hand of a male skier, which was customary for female competitors at the time. Courageous and daring, Isabel broke a world record by jumping a distance of 84 feet. A pioneer for women in her sport, she continued to win championship titles throughout the 1920's.

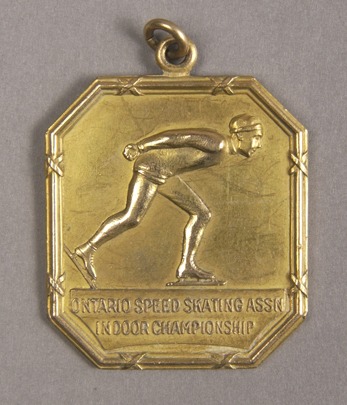

Like Isabel Coursier, speed skating champion Lela Brooks exemplified the bold new spirit of Canadian women who became champion athletes throughout the 1920's and 1930's. Lela maintained a remarkable pace of competition early in her career, racing as often as twelve times in a single day in 1924. In 1925 she earned an incredible 19 national and international championship titles. She broke six world records in 1926 and nearly swept the World Speed Skating Championship by winning three of four events, ultimately capturing the world championship title. Between 1923 and 1930, she won over 65 championship titles in every level of competition, dominating nearly every event she entered, from the 200m to 1,600 m race. Lela Brooks retired in 1935, having claimed every major championship then open to female speed skaters.

Described as "entirely unaffected, supremely modest, completely normal Canadian schoolgirl" who became a "lightning demon" when she took to the ice, Lela Brooks presented Canadians with an intriguing duality. Competing without the benefit of formal coaching, her success as 'the canuck ice wizard' disproved any lingering notions that women were not capable of the speed and strength necessary to succeed in athletic competition. Equally important, like Isabel Coursier soaring off the slopes of Mount Revelstoke, Lela Brooks' unassailable confidence in her own abilities helped usher in an expansive new era of opportunity for Canadian women in sport.

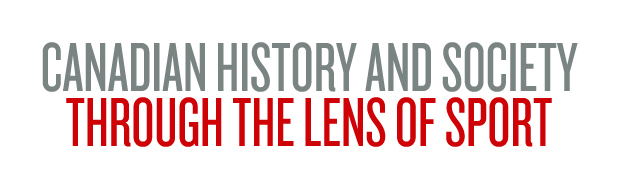

Having won gold medals at almost every level of competition, including this one for the Indoor Championships, Lela Brooks earned the title "Queen of the Blades". She accomplished these feats at a time when women's speed skating was not a well-developed sport. Her pioneering efforts have led to Canada being one of the top speed skating nations today, producing Olympic and World Champions.

Collection: Canada's Sports Hall of Fame

Lela Brooks speed skates had metal tube blades fixed to a leather boot. Today's speed skate, known as a clap skate for the sound it makes, has a blade hinged at the toe, allowing the heel to come up while the blade remains flat to the surface. Lela's honesty and humility won her great respect from her fellow competitors and the public.

Collection: Canada's Sports Hall of Fame

Women competed at the 1932 Olympic Winter Games in Lake Placid in the demonstration sport of speed skating. Brooks and Jean Wilson, who was another of Canada's top female speed skaters, were members of the team that won three medals. Women's speed skating became an official sport at the Olympic Winter Games in 1960.

Collection: Canada's Sports Hall of Fame

Lela had no formal coach and no set training regime. At a time when women were not permitted to join skating clubs her talent was recognized when she became the first women member of the Old Orchard Skating Club in Toronto. She used her talent, perseverance and natural ability to become a champion speed skater.

Collection: Canada's Sports Hall of Fame

Women were ski jumping in Europe as early as 1897 with jumps of 12 metres (39 feet). Isabel Coursier was producing jumps of 25.6 metres (84 feet) in 1922. Pioneering women like Isabel showed their courage, initiative and passion by competing in sport and letting nothing hold them back.

Collection: Revelstoke Museum and Archives

The style of ski jumping has changed over the years. Isabel Coursier is seen here jumping in Quebec, used the upright style with her arms held out for balance. Today's jumpers hold their skis in a V-shape stance for greater lift and hold their body over their skis.

Collection: Revelstoke Museum and Archives

The equipment has changed since Isabel Coursier won her championship title. She used stiff and heavy wooden jumping skis with leather and metal bindings. Her boots were high, laced ones. By contrast today's jumping ski is wider and made of lighter and more flexible materials, allowing the jumper to go farther distances.

Collection: Revelstoke Museum and Archives

Women have competed on an elite international level, starting with the 2009 Nordic World Ski Championships. The World Cup circuit was established in the 2011/2012 season and it became a full medal sport at the 2014 Olympic Winter Games in Sochi. Taylor Heinrich who is a member of the Canadian Women's Ski Jumping team is seen jumping here. She won Canada's first medals at a World Cup. Her victories match the pioneering efforts of Isabel Coursier and have encouraged other female jumpers to continue in this sport.

Collection: Private Collection - Tom Reid, Ski Jumping Canada

Previous Next